A Hybrid Physics and AI Approach to Find Habitable Environments in Exomoon Candidates

ABSTRACT

Background

While searches for life usually focus on a planet’s distance from its star, moons like Europa prove that gravitational squeezing or tidal heating can create habitable oceans far outside that traditional zone. This study analyzes the NASA Exoplanet Archive to find exoplanets that are most likely to have habitable exomoons.

Methods

Using Python, I filtered the archive for large planets at safe distances from their host stars to ensure they could hold onto moons. A physics model calculated the temperatures from starlight and tidal heat, while a random forest AI predicted if the orbits were stable.

Results

The model identified that tidal heating contributed 5% to 18% of the energy for top exomoon candidates. I found that a perfect temperature does not guarantee orbital stability. TOI-2088 b ranked highest, balancing habitability (0.93) with stability (0.95).

Discussion

Tree-based AI models (random forest and gradient boosting) were the most consistent, even when I changed hyperparameters. Changing the orbital paths showed little variation in the surface temperatures of exomoons, suggesting starlight was the main heat source. This study concludes that Kepler-62 f and TOI-2088 b were the best targets for the James Webb Space Telescope to study for potential exomoons

INTRODUCTION

Frequently viewed as just the study of stars, astronomy is also an important tool for solving mysteries of how life might survive in different parts of the universe [1]. For decades, the main approach for finding habitable worlds was to find the “goldilocks zone” or “habitable zone” around a star [1]. This area is a specific distance from the main star where temperatures are just right for liquid water to exist on a planet’s surface [2]. However, our own solar system proves that being “just the right distance” isn’t the only way for a world to be habitable [2]. Moons like Europa and Enceladus exist far outside the habitable zone yet they have huge oceans of liquid water hidden underneath thick ice [3]. These oceans are present due to tidal heating which is determined in this study using the analytical constant Zs to calculate the internal thermal energy [4,5].

In these cases, research has found out that tidal heating, which is caused by friction created when the gravity of giant planets pulls and squeezes a moon during its orbit can be significant [6,7]. However, it is important to note that for tidal heating to stay active for billions of years the planet must have multiple moons to create resonant orbits [8]. The model calculates how the tidal friction combines with stellar radiation to create a stable thermal balance [4,5]. With the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), scientists can now study distant planets and collect data with accuracy [9,10]. This study uses photometric data from the NASA Exoplanet Archive to find potential candidates across thousands of systems [11,12]. A Random Forest Classifier machine learning model is used to determine if the exoplanet data is not just stellar noise [9,10]. This Artificial Intelligence (AI) specifically gave a “Priority Score” to confirm orbital stability inside the habitable zone [13-15].

This study calculates a moon’s total energy by adding the energy the moon receives from starlight and tidal heat [4,5]. This calculation determines if a moon falls within the habitable edge where its temperature is not too hot or too cold and water can exist in liquid form [4]. The hypothesis is that moons can be habitable if they have the potential for liquid water to exist if they have temperatures between 273 K and 373 K [16,17]. In addition, to deal with the uncertainty in exomoon atmospheric compositions and greenhouse effects, this study uses a total radiation level of 100-450 W/m2 as the limit for keeping water liquid [16]. This research aims to identify exomoons that can potentially support life by looking through data from thousands of planets in the NASA Exoplanet Archive, using physics and machine learning [18,13]. The final results provide a list of exoplanets that are most likely to have habitable exomoons that can be studied further.

METHODS

Research Goals and Approach

Due to the small size of exomoons, current telescopes cannot directly see these moons [19,20]. Therefore, physics rules and ML will be used to identify exoplanets that are likely to have moons from the NASA exoplanet archive [11]. If the moon’s surface temperature is in the range between 273 K and 373 K, then it might have liquid water and is considered habitable [16]. To find the moon’s surface temperature, the total heat it receives from the star, the planet and tidal heating is calculated. [4,5] This work will be done in Google Colab using Python to process thousands of planet’s data from the NASA Exoplanet Archive.

Data Steps and Energy Models

Using the NASA Exoplanet Archive, information on thousands of planets will be collected. The dataset will be cleaned by removing planets with missing information [21]. To keep the system stable, the Stability Cascade filter is used [18,22]. Only planets with mass greater than 10 earth masses are chosen because they have enough gravity to keep the moons in stable orbits [4,18]. Also, only planets with an orbital distance between 0.4 AU and 2.5 AU are chosen to make sure the star’s gravity doesn’t pull the moons away [18,22]. Large mass planets will also be capable of having multiple moons which increases the likelihood the orbits are eccentric, which are needed for tidal heating [8,22]. Then, the total energy for each exomoon will be calculated by adding the radiative heat from the star, reflective heat from the planet and internal heat (tidal heat) caused by the planet’s gravity stretching and squeezing the moon [2,4-6].

Machine Learning and Habitability Ranking

Random Forest ML will be used to analyze the NASA exoplanet data to separate real exoplanets from data noise using stellar properties [11,13]. This AI model analyzes which of the physical traits, like distance or mass, most strongly link to stability [14,15]. Google Colab will be used to do the necessary calculations. The result is a ML stability score for each planet which represents the AI’s confidence that a specific exoplanet can actually hold onto a moon for millions of years without gravity pulling it apart. The result is refined to include only moons with surface temperature between 273 K and 373 K [22]. The habitability score ranks exoplanets with potential exomoons by how much their temperatures resemble Earth’s baseline of 288K [23]. The final result is a ranking of exomoons that have a high probability of being habitable and stable without being destroyed by its host star.

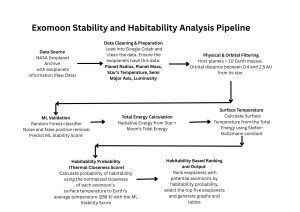

Figure 1: Exomoon Stability and Habitability Analysis Pipeline

Figure 1 shows the Exomoon Habitability Analysis Pipeline. It shows the step by step procedure of the research analysis, from getting data from NASA Exoplanet Archive to the final ranking of habitable exomoons using Python and ML.

RESULTS

Population Selection and Model Output

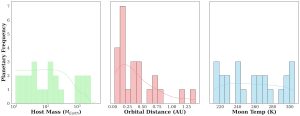

The research identified potential candidates based on model constraints and calculated the potential exomoon’s surface temperature. Figure 2 shows the relationship between these selection inputs and the resulting model output.

Selection Filters (Inputs): The left and the middle graphs represent the main filters used on the NASA Exoplanet Archive. The gravity filter (left graph) identifies all host planets that meet the requirement, greater than 10 Earth mass ensuring they have enough gravity to keep a moon in orbit. The safety zone filter (middle graph) checks the orbital distance of these host exoplanets and is used to find candidates that are between the 0,4 and 2,5 AU orbital range to make sure their moon won’t be pulled away by the star’s gravity.

Thermal Profile (Output): The graph on the right shows the exomoon’s surface temperature calculated for the candidates by looking at the stellar luminosity and planet moon gravitational data. The graph shows that most of the moons are found near 280 K to 300 K, indicating that the selection filters successfully found a population of moons capable of having liquid water.

Figure 2: Multi Variable Selection Criteria for Exomoon Habitability: Gravitational and Orbital Distributions with Thermal Output

Habitability and Stability Mapping

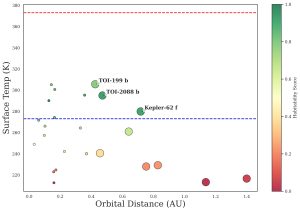

Figure 3 shows the relationship between the calculated thermal results and the predicted orbital stability. The habitability score (green means it is close to Earth’s 288 K) finds exoplanets that can have exomoons with Earth like climates. The size of the dots indicates the ML stability score. This helps filter for exoplanets that can potentially keep their moon in a steady orbit over millions of years. The exoplanets with high habitability sources and high ML stability are labeled on the figure. These are the rare places where it is warm enough for liquid water to exist and also safe enough for the moon to stay in its orbit.

Figure 3: Map of Exomoon Candidates. Thermal habitability scores (color) vs Machine Learning stability priority (size)

Combined AI and Physics Model Analysis

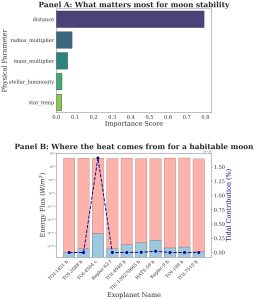

I used a random forest classifier to find what parameters were the best predictors for moon stability. In Figure 4, the AI found that orbital distance was the most important with a statistical score of 78%. The size and mass of the planet and the star’s heat didn’t influence the moon’s stability by much. The moon’s thermal energy comes from two primary sources, external stellar radiation and internal heating created by tidal flux. For the top candidates, tidal flux contributed over 5% of the total thermal energy which shifted some of the moons into the habitable range of 273K to 373 K. In the case of TIC 4672985 b, tidal flux contributed 18% and provided a measurable extra energy boost.

Figure 4: Combined Machine Learning and Energy Analysis.

The top graph shows what are the important factors for moon stability and the bottom graph shows a comparison of the different energy sources that keep the moon warm for the prioritized candidates.

Candidate Ranking

Table 1 shows the data for the most habitable worlds. TOI-2088 b is the highest ranked because it has a high habitability score (0.9336) and also a very good stability score (0.9540).

Exoplanet Name | T_exomoon | Temp_diff | ML_priority | Habitability_Score |

TOI-1451 b | 290.15 K | 2.15 | 0 | 1.0000 |

TOI-2088 b | 295.01 K | 7.01 | 0.954 | 0.9336 |

TOI-4504 c | 295.34 K | 7.34 | 0.002 | 0.9291 |

Kepler-62 f | 279.91 K | 8.09 | 0.968 | 0.9189 |

TIC 139270665 b | 274.29 K | 13.71 | 0.006 | 0.8421 |

HATS-59 b | 271.68 K | 16.32 | 0 | 0.8064 |

Kepler-9 b | 305.18 K | 17.18 | 0.002 | 0.7946 |

TOI-199 b | 305.61 K | 17.61 | 0.942 | 0.7887 |

TOI-7510 b | 266.08 K | 21.92 | 0 | 0.7298 |

TIC 4672985 b | 264.36 K | 23.64 | 0.016 | 0.7063 |

Table 1: Top 10 Habitable Exomoon Candidates Ranked by Thermal Similarity to Earth

DISCUSSION

The Gap Between Temperature and Stability

The results show that the thermal conditions and orbital stability of the exomoons are not related. For example, the model shows that planet TOI-1451 b has the perfect moon temperature of 290 K for habitability. However, its zero stability score could mean that the moon would not survive long term. This is one of the main reasons why machine learning with physics is important to help conduct a reliable analysis.

Limitations: Planetary Flux and Atmospheric Modeling

One of the main limitations of my model is that the planetary radiative and reflective flux are not used when calculating the moon’s total energy. In planetary environments with highly reflective gas giants, factors that contribute to the total heating effect include starlight, radiative and reflected light from the planet and tidal heating caused by the planet’s gravity and stretched orbit. When combined, these sources of heat could increase the surface temperature more than what the current model predicts. My model assumed a constant reflectivity of 0.3 and did not include atmospheric chemistry. Future versions should include light analysis simulations to find greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane. This would improve the accuracy of the model and its temperature predictions.

Reliability and Hyperparameter Analysis

I ran a sensitivity analysis on the hyperparameters to make sure that the random forest AI results were accurate. I modified the number of trees (n_estimators) from 50 to 1000 to test the model. The results stayed consistent even though I changed the internal settings. The top three candidates, Kepler-62 f, TOI-2088 b and TOI-199 b, did not change with the number of trees I used. This shows that the model is reliable.

I also tested my findings using two other AI methods to see if they agreed on which moons were stable. The random forest and gradient boosting methods gave the same results, while neural networks stability scores were all zero. This is most likely due to the small sample size that caused the neural network method to struggle and the results defaulted to zero. The tree based models were the best for the sample size and both of them showed the same top three results (Kepler-62 f, TOI-2088 b and TOI-199 b). This suggests high confidence in the results.

Temperature Test (Eccentricity Sensitivity)

A sensitivity analysis was performed to test if the shape of the moon’s orbit (its eccentricity) would change its temperature. Specifically if the moon’s orbit was more oval shaped or less oval shaped, does it get proportionally squeezed by gravity to increase or decrease its temperature. I halved (0.5x) and doubled (2x) the eccentricity and the results showed that in every single case, for the top 10 planets, the temperature stayed the same. For example, the predicted temperature of TOI-1451 b stayed at 290.15 K for all the three orbits. This suggests that the stellar flux is the main heat source and overpowers any heat created by tidal effects. This test confirms that the habitability scores are accurate because stellar flux is the main factor.

Strategic Target Selection for JWST

The exoplanets that were identified as targets (using data from NASA Exoplanet Archive) were prioritized for analysis. These targets were analyzed for habitable exomoons. We can narrow down potential targets by using combined AI and physics models. Currently, these are performed using expensive systems like JWST. In this study top candidates are identified (like TOI-2088 b) for using specialized tools like JWST’s Near Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) for future studies. Using this model to find orbitally stable candidates first, allows us to get the most scientific value out of expensive telescope observations.

References

- Seager S. Exoplanet habitability. Science. 2013 May 3;340(6132):577-81.

- Eales S. Planets and planetary systems. John Wiley & Sons; 2009 Aug 3.

- Roccetti G, Grassi T, Ercolano B, Molaverdikhani K, Crida A, Braun D, et al. Presence of liquid water during the evolution of exomoons orbiting ejected free-floating planets. International Journal of Astrobiology. 2023 Mar 20;22(4):317–46. doi:10.1017/s1473550423000046

- Heller R, Barnes R. Exomoon habitability constrained by illumination and tidal heating. Astrobiology. 2013 Jan;13(1):18–46. doi:10.1089/ast.2012.0859

- Dobos V, Heller R, Turner EL. The effect of multiple heat sources on exomoon habitable zones. Astronomy & Astrophysics. 2017 May;601. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201730541

- Rovira-Navarro M, van der Wal W, Steinke T, Dirkx D. Tidally heated exomoons around Gas Giants. The Planetary Science Journal. 2021 Jun 1;2(3):119. doi:10.3847/psj/abf6cb

- Kleisioti E, Dirkx D, Rovira-Navarro M, Kenworthy MA. Tidally heated exomoons around ϵ eridani b: Observability and prospects for characterization. Astronomy & Astrophysics. 2023 Jul;675. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202346082

- Tokadjian A, Piro AL. Tidal heating of Exomoons in resonance and implications for +detection. The Astronomical Journal. 2023 Mar 24;165(4):173. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/acc254

- Espinoza, N. and Perrin, M.D. (2025). Highlights from Exoplanet Observations by the James Webb Space Telescope. arXiv (Cornell University). doi:https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2505.20520.

- Feinstein AD, Radica M, Welbanks L, Murray CA, Ohno K, Coulombe L-P, et al. Early release science of the exoplanet WASP-39B with JWST Niriss. Nature. 2023 Jan 9;614(7949):670–5. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05674-1

- Huang S, Jiang C. Machine learning for exoplanet discovery: Validating Tess candidates and identifying planets in the habitable zone. 2025; doi:10.2139/ssrn.5261669

- Rion AH, Any MM. The role of AI in analyzing astronomical data: A literature review. International Journal of Data Science and Big Data Analytics. 2025 Nov 25;5(2):111–6. doi:10.51483/ijdsbda.5.2.2025.111-116

- Rodríguez J, Rodríguez‐Rodríguez I, Woo WL. On the application of machine learning in astronomy and astrophysics: A text‐mining‐based Scientometric analysis. WIREs Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery. 2022 Aug 12;12(5). doi:10.1002/widm.1476

- Akeson RL, Chen X, Ciardi D, Crane M, Good J, Harbut M, et al. The NASA Exoplanet Archive: Data and tools for Exoplanet Research. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 2013 Aug;125(930):989–99. doi:10.1086/672273

- Christiansen, J. L., McElroy, D. L., Harbut, M., et al. 2025, The Planetary Science Journal, 6, 186.

- B Siffert B, G Gonçalves Farias R, Garcia M, Melo de Menezes LF, Porto de Mello GF, Borges Fernandes M, et al. The most common habitable planets iii – modelling temperature forcing and surface conditions on rocky exoplanets and exomoons. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 2024 May 2;530(4):4331–45. doi:10.1093/mnras/stae1150

- Wei 魏 X, Lin 林 DN. Magnetic field of gas giant exoplanets and its influence on the retention of their Exomoons. The Astrophysical Journal. 2024 Apr 1;965(1):88. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ad2843

- Szabó GM, Schneider J, Dencs Z, Kálmán S. The “drake equation” of Exomoons—a cascade of formation, stability and detection. Universe. 2024 Feb 28;10(3):110. doi:10.3390/universe10030110

- Teachey A. Detecting and characterizing Exomoons and exorings. Handbook of Exoplanets. 2024;1–49. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-30648-3_211-1

- Heller R, Hippke M. Large exomoons unlikely around kepler-1625 b and Kepler-1708 b. Nature Astronomy. 2023 Dec 7;8(2):193–206. doi:10.1038/s41550-023-02148-w

- Banerjee P, Chattopadhyay AK. Habitable exoplanet – a statistical search for life. Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences. 2025 Dec 1;12. doi:10.3389/fspas.2025.1674754

- Patel SD, Quarles B, Weinberg NN, Cuntz M. Tidally Torn: Why the most common stars may lack large, habitable-zone moons. The Astronomical Journal. 2025 Dec 4;171(1):11. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ae1b8c

- Nikouravan B. A comparative evaluation of earth similarity index (ESI) methods for Exoplanet Habitability Assessment. Hyperscience International Journals. 2025 Sept;5(3):63–9. doi:10.55672/hij2025pp63-69